Tag: Facebook

Platform Capitalism and the Government of the Social. Facebook’s ‘Global Community’

Some days ago, Facebook’s CEO and founder, Mark Zuckerberg, published on his page a letter where he makes some very interesting statements about the ongoing direction of the platform, its current priorities and the general vision underlyng its strategy of development. The document has been mostly and inevitably read against the larger debate on how the largest of the global social media platforms has changed political communication.

Actually, Zuckerberg does address in the letter two of the most frequent charges which have been moved to the gigantic social networking site by its critics. The first allegation claims that Facebook creates ‘filter bubbles’ and ‘echo chambers’, that is that it exposes its users only to similar opinions (what Zuckerberg names the problem of ‘diversity of viewpoints’, and the ensuing polarization of the political climate). The second accusation concerns the ways in which the medium allegedely does not make a difference between false and true information (as in the virality of ‘fake news’), defined by the American billionaire as the risk of ‘sensationalism’. Defining these issues as basically a question of ‘risks’ and ‘errors’, Facebook promises to invest more into its Artificial Intelligence program, announces great progresses in its capacities to increasingly distinguish ‘true’ and ‘false’ news while also promising to tweak its algorithms to increase the diversity of its users’ feeds – thus addressing the problem of misinformation and political polarization. In addressing these criticisms, what seems to me most significant, however, is the way Facebook seems to admit to be in the unprecedented position to govern the global social life of information, thus becoming the new infrastructure of a transnational, (post)civil society.

It has been quite a change lately from the days when Facebook, following Google in this regard, rejected the idea of being a media company, defining itself first of all as a high tech company. By acknowledging its responsability in creating the social environment or medium where political communication unfolds, Facebook is starting to look more like a medium, hence facing the kind of issues that the news media such as TV or the press have to deal with, such as bias or misinformation. The letter reads as Facebook’s admission that it is willing to take on the political responsability to govern its platform. Technology companies are not new of course to governance – an issue which is keenly felt by businesses operating in the areas of the Internet of Things, Smart City, the Sharing Economy, the Gig economy and so on. Facebook, however, sees itself in the position to regulate what the letter defines as the ‘social fabric’ woven by processes of association and dissociation and the ‘collective values’ that emerge from such processes.

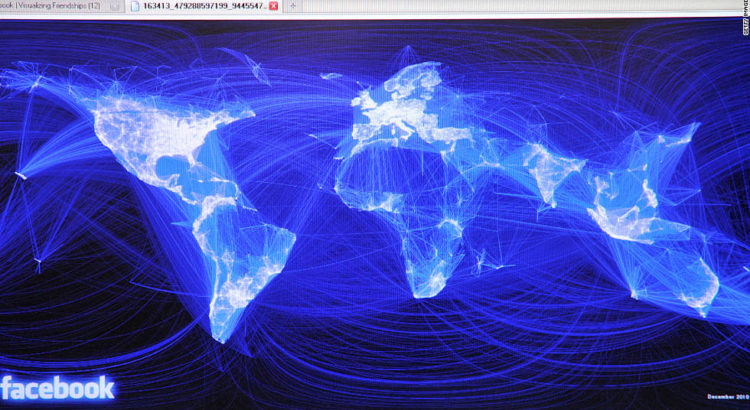

In the aftermath of Trump’s victory, with the possible exception of Uber, mostly Silicon Valley companies have positioned themselves with the opposition, presenting themselves as the stalwart representatives of both American liberal values and globalization (the letter closes with a quote from Abraham Lincoln). If Facebook’s mission is ‘to make the world more open and connected’, then it is a mission which does not agree well with the nationalist closures indicated by events such as Brexit or Trump’s election. The letter presents Facebook as engaged in weaving of a global social fabric which is not homogeneous, but composed of overlapping and yet culturally specific parts. The heterogeneous transnational cultures which make for Facebook’s social fabric produce variable cultural norms, which cannot be determined or governed starting from a single norm. A normative, variable and differentiated curve, such as that described by Foucault in his discussion of mechanisms of security, displaces ‘normality’, while openness and connectedness realize the continuity of economic valorization. (Almost) the whole world, or at least those parts that are ‘open and connected’ is now the ‘inside’ of Facebook – literally lying side by side in its servers.

In the aftermath of Trump’s victory, with the possible exception of Uber, mostly Silicon Valley companies have positioned themselves with the opposition, presenting themselves as the stalwart representatives of both American liberal values and globalization (the letter closes with a quote from Abraham Lincoln). If Facebook’s mission is ‘to make the world more open and connected’, then it is a mission which does not agree well with the nationalist closures indicated by events such as Brexit or Trump’s election. The letter presents Facebook as engaged in weaving of a global social fabric which is not homogeneous, but composed of overlapping and yet culturally specific parts. The heterogeneous transnational cultures which make for Facebook’s social fabric produce variable cultural norms, which cannot be determined or governed starting from a single norm. A normative, variable and differentiated curve, such as that described by Foucault in his discussion of mechanisms of security, displaces ‘normality’, while openness and connectedness realize the continuity of economic valorization. (Almost) the whole world, or at least those parts that are ‘open and connected’ is now the ‘inside’ of Facebook – literally lying side by side in its servers.

A few years ago, authors such as Celia Lury and Maurizio Lazzarato among others, described the change by which post-Fordist businesses do not primarily produce goods, but are engaged in the production of worlds to live in. Here Zuckerberg presents the mission of his company as emtailing a ‘journey’, which involves the creation of a world, obviously open and connected, which realizes the long journey of humanity towards wider and wider forms of social aggregation: from tribes, to cities, to nations, and now, thanks also to Facebook, to a ‘global community’. There is of course more than a a Eurocentric hint of linear progress at work, an arrow of time pointing to the destiny of a global society. Facebook thus presents itself, implicitly like the Silicon Valley as a whole, the historical representative of the forces of globalization which oppose the nationalist closure of Brexit and Trump. Facebook’s mission then becomes implicated in facilitating and expanding globalization as a process which presents ‘challenges’, ‘risks’ and ‘opportunities’ which no single nation or people can take on but that need the mobilization of a ‘global community’.

The overall focus of the letter is thus on the challenge of building new ‘social infrastructures’ which enable the global community to get organized and to strengthen the ‘social fabric’ paradoxically compromised by globalization. It’s interesting to notice how this intention to build a global political community is given by data on the growth of ‘groups’ in Facebook. The focus on groups triggers a shift of attention from interpersonal networks (friends and family) and pages (which are the engines of economic valorization with their ‘likes’) towards ‘groups’ as priority for future investment. This shift to groups returns Facebook to questions asked by the inventor of sociometry and of the ‘social graph’, the psychiatrist Jacob Moreno who in th e mid-twentieth century posed the problem of mapping ‘the mathematical properties of the psychological life of populations’ – that is of the psychosocial regulation of social life starting from groups.

e mid-twentieth century posed the problem of mapping ‘the mathematical properties of the psychological life of populations’ – that is of the psychosocial regulation of social life starting from groups.

The question of groups allow for the formulation of the vision and model of society which Facebook proposes as the solution to the global crisis of governance (but significantly not the economic crisis). I am convinced that it is not by chance that the question of the ‘social infrastructure’ has risen around the popularity of groups, and in particular what Zuckerberg defines as ‘very meaningful groups’ which quickly become an essential source of support and identification for those who join them. Unlike interpersonal or egotistic networks (friends, family and acquaintances), groups take us back to the old image of the caring ‘virtual community’ which Howard Rheingold described in the early 1990s. The old virtual community is here integrated into a ‘global social fabric’ which is also an infrastructure which is the platform as a whole. Facebook’s communities or groups are by far the only ways by which communities form on the Internet, but what the company seems to claim is they are in a privileged position to enable such processes within a single, private network with a centralized, cloud computing architecture which hosts a population of a couple of billions of accounts modeled according to the diagrams and methos of graph theory and social network analysis. Such social is not significantly conceived as essentially made of isolated and connected individuals (alone together as Sherry Turkle put it), but as composed of groups and sub-groups. I would argue that in social networks, the individual is always somehow defined by the groups it can be seen to belong too in as much as there is no individual in a social network who exists if not as part of a group – even the smallest group of two. The model of society evoked by Zuckerberg under the name ‘community’ is a set of connected sub-sets, topologically discrete and yet continous which returns the image of an heterogeneous and entangled planet. Implicitly evoking the fist social network analysts, Zuckerberg describes society as a granular fabric of unevenly sized communities, which merge and differentiate, but within a single plateau provided by the platform’s body. One has the impression that it is this specific composition which allows for the social network to become in Zuckerberg’s vision the problem-solving infrastructure of global crises, significantly and mainly identified with terrorism and climate change.

Some years ago, anthropologist and activist Joan Donovan told me how the Occupy movement managed to use and orient politically the logistical capacities of social networks, that is their capacity to change from networks where opinions are shared to networks able to coordinate action at a large scale. When the Sandy hurricane hit New York City, she told me, Occupy managed to collect and distribute resources, thus proving the capacity to produce an autonomous government of emergencies, which national and local government are increasingly inadequate to do because of the budget cuts. In the letter, Zuckerberg keeps quoting examples of such uses of the platform autonomously organized by users, by the intelligence of the general sociality captured by such media. As the number of individuals and groups engaged in thinking and experimenting with p2p and/or -social production grows, Donovan has started to define ‘hypercommon’ the potential of the technosocial to cooperate and govern in ways which differ both from the market and the State’s modalities of government.

Significantly, Zuckerberg does not include in the list of political priorities for the global community the debt crisis, precarity, exploitation or forced migration, but stops at pandemics, terrorism and climate change. The platform thus becomes the was in which an emerging global society defends itself against ‘harms’ and prevents them. If the platform is positioning itself as an alternative to the extreme nationalism of Brexit and Ttump, it does so remaining firmly within the boundaries of what Nick Srnicek has called ‘platform capitalism’ – which will be discussed early in March in an event organized by the free university network of postworkerist inspiration, Euronomade, in Milan’s ‘liberated’ space Macao.

To sum it up, for me this letter makes it even more clear how Silicon Valley is formulating what Foucault would describe as a new ‘political rationality’ which takes on the legacy of liberalism and neoliberalism in identifying as the main problem the government of populations (billions of users), the maximisation of their social, political and cultural life, and the protection from ‘’risks’, ‘harms’ and ‘errors’ inherent in the circulation of information (false news, sensationalism, polarization, divisiveness, terrorism, climate change and pandemics). This is accomplished within a market economy that never questions ownership or accumulation. Together with the smart city movement, platform capitalism intensifies its vocation to become a new form of social government.

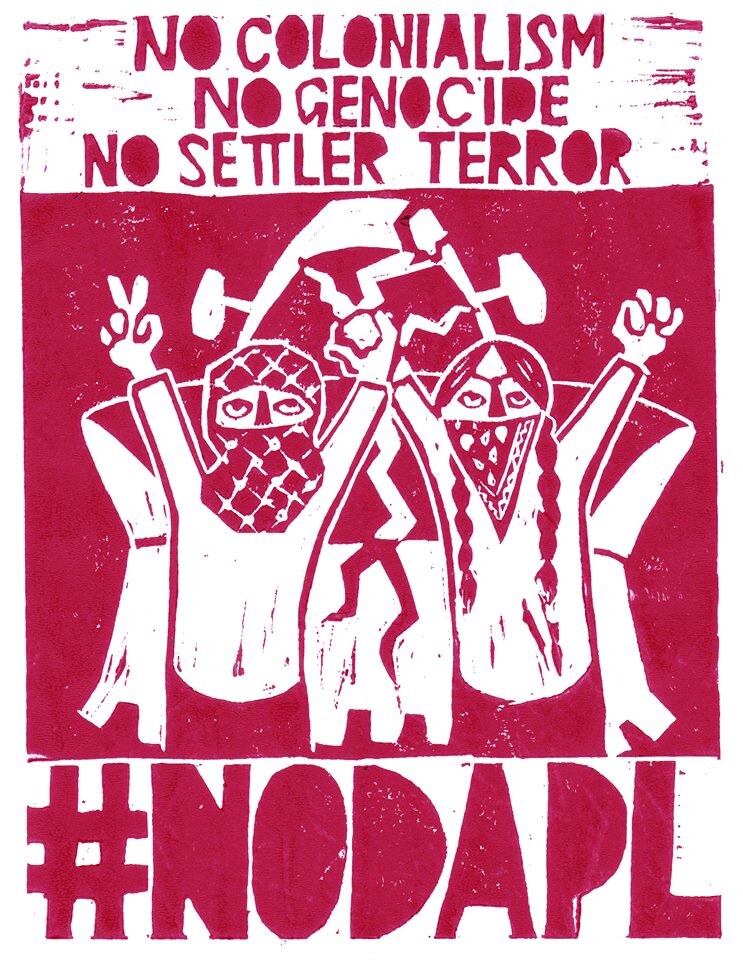

Da Standing Rock alla Palestina: Facebook tra la solidarietà e la sorveglianza

“Arrived safely. PM me for your concerns. We’re gonna beat back the Feds! Solidarity always.”

We stand with Standing Rock. A queste parole si è accompagnato più o meno l’ondata virale di post e check-in su Facebook dei giorni scorsi. Pare che oltre un milione di persone abbiano infatti scelto di geo-localizzarsi pubblicamente nei pressi della riserva indiana di Standing Rock, nel North Dakota, Stati Uniti d’America. A scatenare la reazione globale è stato un post, la cui origine sembra essere difficile da decifrare ma che è transitato attraverso i canali Facebook della Standing Rock Indian Reserve, la comunità resistente Sioux che si oppone alla costruzione sul suo territorio dell’oleodotto (Dakota Access Pipeline). Nel post si faceva riferimento al fatto che le autorità e lo sceriffo della contea stavano utilizzando lo strumento check-in di Facebook, grazie al quale è possibile registrarsi ed essere registrati in qualsiasi posizione geografica, per monitorare, individuare e localizzare gli attivisti, in centinaia già arrestati durante gli scontri con la polizia. Perciò i “Water Protectors” hanno richiamato la comunità transnazionale di solidali, chiedendo di registrarsi lì e condividere pubblicamente la localizzazione, così da ingarbugliare il sistema e confondere le autorità di polizia, un’azione quindi concretamente utile a proteggere tutti coloro impegnati fisicamente in prima linea nella difesa del territorio e delle risorse.

Se e quanto un’operazione di questo tipo possa essere effettivamente utile all’obiettivo dichiarato sembrerebbe difficile da definire, ma potrebbe non essere in realtà l’aspetto più significativo di questo discorso; sarebbe più importante ragionare sui due aspetti intrecciati della questione, ovvero l’uso di Facebook come strumento di controllo, sorveglianza e indagine da parte delle autorità di polizia, dall’altro la possibilità – forse – di poter ricorrere allo stesso strumento in maniera sabotante per innescare meccanismi di solidarietà, più che di resistenza. È chiaro che gli attivisti in North Dakota sono per lo più preoccupati dal monitoraggio diretto che da quello virtuale, così come è chiaro che, se veramente Facebook è adoperato a questo scopo, non sarà difficile distinguere le localizzazioni reali e magari non pubblicizzate, da quelle da remoto di questi giorni. Tuttavia, nonostante lo sceriffo della contea di Morton abbia pubblicamente negato questa pratica di controllo digitale, l’utilizzo dei social media come strumento di intelligence non è certo una novità, e l’abbiamo visto negli Stati Uniti anche nei confronti degli attivisti del movimento Black Lives Matter.

L’esperienza di Standing Rock ci dà modo di ripensare in qualche modo quella dei Territori Occupati Palestinesi. Che i due territori e le due comunità siano legate a doppio filo dalla necessità di fronteggiare l’avidità di un potere che si manifesta nelle forme di un colonialismo di insediamento (settler colonialism) sempre in fase espansiva, simbolicamente rappresentato dallo strumento del Caterpillar, di cui ha parlato Léopold Lambert sul suo blog The Funambulist; e che non a caso la comunità palestinese abbia in questi giorni lanciato un appello di solidarietà con le comunità indigene in lotta, è una delle parti più interessanti di questa storia, e che di certo andrà approfondita altrove. Un legame che fa da esemplare cornice a come un potere di matrice coloniale usi anche la sfera digitale per incidere, affermarsi e invadere lo spazio, coniugando la finalità di appropriazione con la necessità di dominazione e sorveglianza.

Sappiamo forse poco di Standing Rock, sappiamo però di BLM, così come sappiamo che non è una pratica desueta quella dei servizi di intelligence israeliani di usare Facebook non solo per monitorare il dibattito interno palestinese, ma anche per riuscire ad ottenere delle informazioni. Nell’ottobre dello scorso anno, nel pieno delle manifestazioni e degli scontri tra giovani palestinesi e militari israeliani, si diffuse la notizia che Israele si stava servendo di finti account palestinesi (creati ad hoc e raffiguranti bandiere palestinesi come immagini di copertina, con testi scritti in arabo e numeri di telefono locali) per riuscire a scoprire i nomi e i numeri di telefono di coloro che prendevano parte agli scontri con le forze israeliane in Cisgiordania. Questa forma di intromissione porta ad un livello superiore quello che è ormai una strategia solida, quella per cui pagine e profili personali di personaggi in vista vengono chiuse per violazione delle regole di Facebook (segnalate dagli stessi account fake che sono stati creati), o che ha portato in giudizio palestinesi accusati di aver fomentato la violenza con i loro post su Facebook, adducendo come prove l’attività degli stessi sui social network. È evidente quanto per un governo ossessionato dalla paranoia e dalla sorveglianza, e quindi caratterizzato da un fortissimo investimento tecnologico e un grosso expertise nel settore della cybersecurity, ma soprattutto con il totale controllo delle infrastrutture di telecomunicazione su tutto il territorio (Gaza e Cisgiordania comprese, nonostante il servizio sia poi appaltato a società palestinesi – la situazione è descritta in maniera interessante nei lavori delle studiose Helga Tawil-Souri e Myriam Aouragh), il crescente utilizzo di Facebook anche da parte della comunità palestinese non ha fornito che il pretesto per l’introduzione di nuovi metodi e nuovi terreni dove esercitare il proprio controllo. Le agenzie di sicurezza israeliane considerano Facebook una sorta di “open source information”, dove recuperare informazioni senza dover essere a rischio sul campo, e pare che solo poche settimane fa il Ministro della Giustizia israeliano abbia incontrato i vertici dell’azienda di Facebook per coinvolgerli in una task force contro i contenuti che incitano alla violenza contro Israele. Dietro la superficie pacificata di un accordo in risposta ad hate speech ed istigazione della violenza, c’è dunque il malcelato tentativo di assumere una posizione asimmetrica e di esercizio repressivo in quello che è diventato in qualche modo l’ennesimo fronte, stavolta virtuale, di questo conflitto, e per tentare di arginare tra l’altro l’espansione della campagna BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions), che proprio anche grazie alla rete di Internet si alimenta.

Certamente, quest’ultimo evento solleva anche un punto importante sul ruolo, le collaborazioni e le responsabilità di un’azienda proprietaria e tendente al monopolio come quella di Facebook, generando ulteriori interrogativi su cosa succede quando ad essere merce di scambio o di vendita non sono solo i big data. Nel caso palestinese però, è bene notare che Facebook non emerge che come la punta dell’iceberg di una pratica di controllo ben più stratificata, che passa come si accennava per la digital occupation, e cioè il controllo delle infrastrutture di telecomunicazioni, e si insinua anche attraverso quello che Adi Kuntsman e Rebecca Stein hanno chiamato digital militarism, quel processo per cui la cultura militarizzata della società israeliana penetra le politiche del quotidiano attraverso i social media, contribuendo tra l’altro a sedimentare una percezione derealizzata dei palestinesi, da parte militare e civile.

La situazione palestinese nella sua complessità, e quella di Standing Rock nella sua piccola ma simbolica esperienza di controllo digitale, devono quindi indurre a ragionare anche su scale un po’ più ampie, senza dover necessariamente però ricadere nell’idea che ogni tentativo di porre resistenza o seminare solidarietà debba risultare inquestionabilmente indebolito o vanificato. Se Facebook può agire come un motore di accelerazione, non costa nulla pensare che questo possa succedere a Standing Rock grazie ora ad una maggiore attenzione della comunità globale. In questo caso l’operazione di dirottamento e détournment operato dalla comunità solidale a Standing Rock, se forse non è del tutto incisiva allo scopo di depistare le presunte indagini della polizia, è riuscita però a forare la bolla e a dare un senso politico ad una funzione banale e abusata – quella della localizzazione, riappropriandosi – certo parzialmente – dello strumento di Facebook. Indubbiamente, la solidarietà non risiede in un tag o in un like, che possono risultare effimeri se non sostenuti da una più profonda, ed anche materiale, attività di supporto, ma se la possibilità che nuove narrazioni autonome emergano e trovino spazio nel caos della rete è ancora un nodo cruciale, e se localizzarsi può servire a diffondere informazioni e generare azioni di solidarietà, allora si fa importante contribuire alla loro diffusione, da Standing Rock alla Palestina.