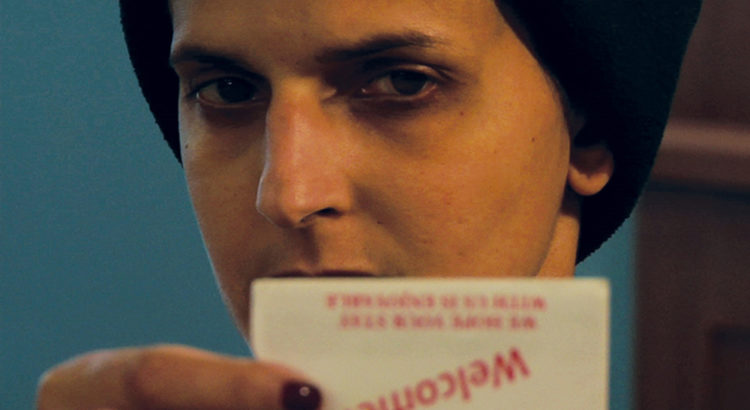

Dying for the Other (2012) [is] a video tryptich in the form of a three-screen installation shot in 2011 in the three months following Beatriz da Costa’s brain surgery. The video is part of the multimedia project The Cost of Life (2009–2012) which, as the title suggests, wonders about the value of life in between nature and culture, the individual and the environment. […] The simultaneous projection of Dying for the Other starts from the central of the three adjacent screens, where the letters of the central part of the title, ‘for the’, slowly start appearing in transparency, imitating a window decal, so that the viewer glimpses some moving figures behind the glass only the movements of which are distinguishable, not the shapes or the setting. After the words ‘Dying’ and ‘Other’ slowly materialise left and right, a fade-out to white leaves again the scene to the central screen, where in the place of ‘for the’ we now see a half close-up of da Costa, accompanied by a man beside her, who very slowly and unsteadily walks with an intent gaze along what looks like a hospital corridor, trying to keep an imaginary straight line in front of her.

The place where dying happens and the place of the other, that the words ‘for the’ relate in the video work, are not fixed ones. Sometimes we see da Costa in the place where dying happens, sometimes she is the other living in the place of the mice who die in the lab. A continuous interference is created by combining and alternating these images. For example, at the beginning of the video, while we look at the image of the artist walking along the hospital corridor, all at once, on the lateral screens, two slightly different angled images of the same mouse, kept in the hands of a lab scientist while injected, appear for a moment to disappear right after. Later, behind the façade of the American Cancer Society Hope Lodge Jerome L. Greene Family Center in New York, whose door da Costa has just entered in the previous sequence, we meet the same researcher perfectly at ease in a laboratory, her movements quick and precise, handling a series of tools that resemble the objects of a domestic kitchen: a fridge, a stack of (petri) dishes, a dropper, several plastic and glass bins, and the mice, that appear again while taken from a cage to be injected, as well as while lying on a digital scale.

Without even realising it, as the cold light and colours remain more or less the same, the plastic case that we now see in the central frame is da Costa’s pillbox, hers the hands that sort the pills into the little boxes assembled in a row that serves to organise the cure on a weekly basis. A kitchen, again, but da Costa’s this time, with the artist organising her groceries and chopping kale, but also cutting her pills in half on a ceramic plate, beneath the highly disturbing image of a glass cage with what look like agonising mice inside. […]

Another disturbing interference takes place when we see the artist doing yoga and stretching on the floor virtually beside the researcher who first ‘stretches’, then dissects the mice bodies on the table to isolate their tumours and then extract them from their bellies. In the following scene, the researcher, having put the tumour on a petri dish, tries to keep it still with tweezers and to cut it open with a scalpel, at the same time that she, using a childish tone, underlines how ‘teeny-tiny’ the tumour looks – paradoxically, Haraway uses the same expression, but in a completely different meaning, noting that da Costa has learned to ‘co-habit with the teeny-tinies’ since her early projects. When the artist is shown while she exercises with her partner and tries to repeat sequences of numbers and words backwards, her shaky efforts with ordinary words contrast with the extreme self-confidence of the researcher who explains her procedure in the lab. However, when we compare the researcher’s attempts to cut the tumour with da Costa’s cutting her pills in half, this time the hands of the researcher seem hesitant, whereas da Costa’s gestures appear firm and precise.

[…] Incidentally, hands are the most focalised body part in the tryptich. We see hands that hold, manipulate, cut, sort, squeeze, reach out, hands that do things, hands that kill and hands that cure, hands that kill to cure, hands that cure without killing, connecting hands and separating ones. In fact, hands shift the attention of the observer from the eye’s contemplation to the hand’s intervention. Through hands, emphasis is put on enacted practices. Formally, the three screens projecting the synchronised video sequences reinforce the invitation to articulate vision and at the same time to be wary of such articulations […]. The representation of disease is distributed outside of the enclosed space of a single frame, which at the same time links the image of the artist’s site and that of her disease to other diseases and other sites, establishing a series of visual connections that refer to material ones, and reinserting the personal dimension of disease in a broader frame.

In Dying for the Other, the preposition ‘for’ works as the conjunctive term that foregrounds the reversible relation of biopolitics and necropolitics, of the dying and the living, of the partners that do not precede their relations but are the other of each other. The mice are significant others for da Costa, but at the same time, da Costa as cancer patient plays the same role for the mice, as does da Costa for other cancer patients that she stands for, and also for the art audience for whom she ‘represents’ her story […]: in fact da Costa’s witnessing of her own story never disjoins from ethical attention for those ‘companion species’– be they bacteria, animals, human beings or technical tools – that share with the artist, and with us viewers, their stories of ‘co-constitution, finitude, impurity, historicity and complexity’. The artist acknowledges such multiplicity as being already inside her body, a difference within that, diffracting the body through itself, poses the existence of exteriority in terms of relation rather than separation. It is not by chance that in many scenes da Costa wears a black cap and a very iconic black dress whose cuts, beyond resembling a skeleton chest case in a sort of memento mori, also evoke animal shapes, as if she were wearing a spider’s legs or the striations of a butterfly’s wings.

As Catherine Lorde notes in her conversation with Haraway on the occasion of the exhibition dedicated to da Costa at the Laguna Art Museum in 2013, more than ‘who the other is’, the question ‘to what, exactly?’ is paramount here. This latter question, apart from shifting the focus from identity to alterity, also reframes alterity as a material becoming, or better, as a becoming with. In a sense, Dying for the Other speaks about what it means to become with the other in practice, where practices, in this case, are the words, gestures, technologies, times and sites of dying […].

Sites are locations where connections are either stabilised or mobilised in practices, but do not stand still. Thus, according to Mol (The Body Multiple, 2002), the proper question should be: ‘What becomes of objects when practices interfere with one another’ (p. 121). This is why the artist also stands as the significant other of the lab scientist, and the artwork the significant other of the lab work. Actually, since the practice of art and the practice of science are ‘natural sibling practices for engaging companion species’, as Haraway states (When Species Meet, 2008, p. 22), da Costa assumes a declaredly partial, situated position as a ‘modest witness’ (Haraway, Modest Witness, 1997) that interferes with the apparently neutral scientist’s position. Her seeing attests to the responsibility of taking a position in relation to the other, in contrast with the supposed objectivity of testing that the scientific lab conveys, which is questioned by the continuous interferences that this work creates.

[…] Balance characterises Dying for the Other, both at a technical and narrative level: the arranged comparisons and contrasts, the calculated alternation of visual angles, the shifts between subjects and places. Combined with interference and propagation, however, balance is never represented as an already conquered equilibrium, but as a dynamic tension which implies work […]. The ordinary stability of life is the performance of a series of successive and successful repetitions (see Butler, 1990). Specifically here, life seen through the lens of disease, and also diffracted through laboratory practices, loses its carefree naturalness and is shown to be built up throughout a constant maintenance work of natural-cultural concatenations.

Let us take, for example, the OncoMice™ that Haraway (1997) talks about, patented animals classified in databases and even sold in catalogues that, like other material-semiotic hybrids such as genomes, acquire a status of ‘second-order objects’, as Haraway calls them (p. 99): beings that are made, although not made-up. In fact, their alienable bodies are the product of ‘a mixture of labor and nature’ (Haraway, How Like a Leaf, 2000, p. 140), and for this reason, they need undergo periodic controls to see if they still fit the research aims, given that sometimes their genes can get lost in cell division and such mutations make them useless for experimentation. So, their identity is the outcome of a ‘labor of maintenance’ in which they are treated ‘as if they were microprocessor chips’ (p. 146). But da Costa’s life as cancer patient appears to be the same: actually, ‘mice and humans in technoscience share too many genes, too many work sites, too much history, too much of the future not to be locked in the familial embrace’ (Haraway, 1997, p. 100).

What changes, however, is that the alienating processes through which OncoMice™ are made and subjected are instead diffracted by the artist through her embodied location in the story. This allows her to show how the maintenance of all life forms puts forth the necessary coimplication of multiple actors in the process. This is the sense in which Haraway talks of Dying for the Other as a work about ‘assisted living’, in which life can go on because it is distributed among several companions, including non-human ones, like animals (the lab mice, but also da Costa’s dog that we don’t see but which Haraway explains was trained to help her move around), plants (the healthy vegetables that da Costa buys and cooks), and objects (for example the walker that she needs to go outside).

[…] In fact taking multiplicities apart, or rather making them ‘implode’ in a whole array of practices (Haraway, 1997, p. 68), reveals how practices as well as bodies do not organically or even mechanistically cohere, but rather assemble in open ecosystems. Like Guattari’s (Chaosmosis, 1995) biological and nonbiological machines, they are able to organise themselves; however, their autonomy is never, properly speaking, closed, since relations of alterity lead to a continuous ‘disequilibrium’, implying a ‘radical ontological reconversion’ (p. 37). Being, the being of such assemblages, is thus giving – that is, being for alterity rather than for the self. It is a generative process in which differences ‘envelop each other’ (p. 111) […] Living and dying is not only for the other, but also with the other and with/in another. Thus, being cured and assisted also necessarily means assisting in turn, paying attention, taking care, being respectful. After all, as Haraway (2008) underlines, this is the sense of looking at our companion species. Actually, species, seeing and respecting all share the same etymology […]