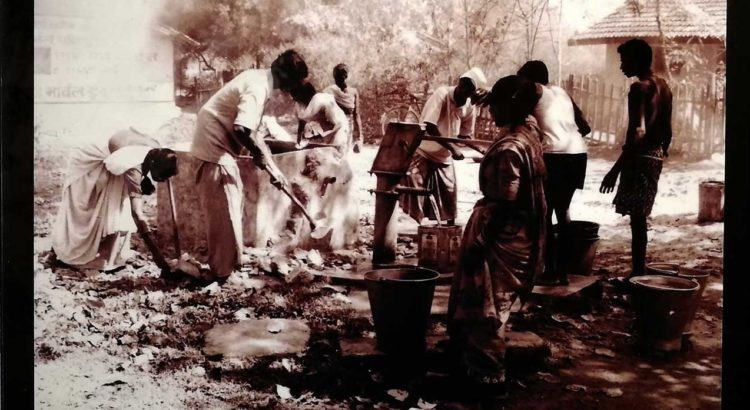

[/caption]Gli argomenti che propongo risalgono in buona parte a quelli della critica alle istituzioni che dagli anni Sessanta in poi ha riempito, a livello globale, molte pagine, eventi, manifesti politici e culturali. Da quel momento il rapporto tra rappresentanza e rappresentazione è profondamente mutato e “non c’è più l’aspirazione a impadronirsi dello Stato (o dei suoi istituti come il Museo, il Partito, il luogo del Lavoro, etc.), piuttosto […] un’attitudine a difendersi e a uscire da esso […]. “Exit” […] non “Voice”: abbandono anziché scontro. Ricerca di nuovi spazi d’intervento, di immagini costituenti, di micro-azioni su scala locale, di forme di autogestione, di autoorganizzazione, di empowerment.” (Scotini 2009, p. 101). Oggi le condizioni generali sono ulteriormente cambiate e ancor più complicate; ciò di cui abbiamo bisogno sono visioni e pratiche che ci aiutino a resistere alla tossicità dell’antropocene e del capitalocene. Perciò, a maggior ragione, credo che una relazione costante – non-formale e non-gerarchica – tra arte e attivismo, oggi più che mai, vada incoraggiata. Lo penso tutte le volte che visito una mostra che si fa vanto dei suoi contenuti sociali o politici ma che allo stesso tempo, per elaborarli, non ha fatto altro che espropriare e inquadrare le soggettività che di quei contenuti diventano forzatamente dei meri contenitori (vedi le numerose ‘vittime’ prodotte dalle molte mostre pseudo-antirazziste della sinistra multiculturalista, incentrate – ancora – sull’ “autenticità africana” o sulla migrazione o sui soggetti socialmente “deboli”). Lo penso quando alcuni spazi dell’attivismo sembrano soffrire di scarsa visionarietà, quella per cui non si riescono a sperimentare forme, modi e linguaggi insoliti, non-previsti, potenzialmente non-catturabili (le esperienze transfemministe e queer fanno spesso eccezione). Soprattutto, lo penso quando mi muovo in contesti non identitari e contaminati, dove l’artista e l’attivista non sono più figure sacre o etichette da sfoggiare, ma pratiche e modi indipendenti da ogni vincolo e orpello. Per tornare al dunque, lo penso quando visito mostre come quella di Altaf – anche se finanziata da un istituto bancario; anche se fatta per lo più di riproduzioni al posto di opere originali: l’aura dell’unicità è evaporata e si è portata via il pregiudizio dei puri. Le tecnologie digitali e le tecniche hanno dato il loro contributo disintossicante. La dissacrazione è compiuta.

In un saggio del 2009 in cui parla del suo progetto Disobedience – an ongoing videoarchive, Scotini si interroga sul significato della disobbedienza (sociale) e su quale potenziale discorsivo potrebbe avere la sua “messa in scena”, o in mostra. Dalla scrittura di quel saggio sono trascorsi più di dieci anni, durante i quali il curatore ha continuato a disseminare il suo contributo critico, prestando attenzione alle esperienze politicamente e socialmente “costituenti” presenti in Italia (incredibilmente attiva dagli anni Settanta in poi – dall’arte povera alla critica femminista; da esperienze come Agricola Cornelia di Gianfranco Baruchello al PAV di Piero Gilardi) e a quelle che si muovono nel resto del mondo. Mentre oggi è del tutto irrilevante stabilire se la pratica di Altaf possa definirsi o meno “costituente”, o se essa abbia diritto a entrare nell’archivio delle pratiche disobbedienti, mi sembra molto più interessante tornare a chiedersi “se le forme di presentazione di una mostra politica possano sviluppare nuovi modelli di dialogo, di ricezione, di interazione, di critica, di azione comunicativa. È importante capire – continua Scotini – fino a che punto possano forzare i limiti del sapere disciplinato; fino a che punto trasformarlo in un campo di scontro simbolico.

Proiettando questi interrogativi sul caso Samakaalik: può la forma di presentazione di questa mostra stimolare nuovi modelli di dialogo, ricezione, interazione, critica, azione comunicativa? Che significato può assumere e quale potenziale discorsivo può esprimenre il suo soggetto ‘rivoluzionario’ in un paese in cui si fa ancora fatica a riconoscere il proprio passato coloniale; in cui un vero processo di defascistizzazione non si è mai compiuto e l’impronta economica, sociale e culturale che tutti i governi stanno ricalcando è quella impressa dalle potenze egemoniche – di stampo capitalista, classista, sessista, razzista, specista?

Ad argomentare delle risposte mi aiuta in parte Judith Butler, quando riprende Susan Sontag per parlare di “obbligazione etica”, ovvero della nostra capacità di rispondere a distanza in maniera etica alla sofferenza, e di cosa rende possibile questo incontro etico, quando esso ha luogo:

“[…] ciò che sta accadendo è così lontano da non investirmi di nessuna responsabilità? Oppure, al contrario, ciò che sta accedendo mi è tanto vicino da costringermi a occuparmene? Se non ho causato io, in prima persona, questa sofferenza, vuol dire che non ne sono in alcun modo responsabile? […]”

(Butler, L’alleanza dei corpi, p. 162).

Personalmente, la visione della mostra mi ha provocato un cortocircuito lento e progressivo, scattato nel momento in cui i suoi contenuti si sono sovrapposti all’attuale situazione politica italiana – quella di governo, da una parte, e quella dei movimenti, dall’altra.

Può la mostra di Altaf provocare un qualche tipo di risposta etica nel suo pubblico? Certamente “oggi sappiamo cosa significa sentirsi invasi e sopraffatti da immagini che fanno appello ai nostri sensi; ma lo siamo anche da un punto di vista etico? […]”. E poiché sappiamo che le immagini sono in grado di sopraffarci e paralizzarci, è possibile, invece, “sentirsi sopraffatti, ma non paralizzati? […] la sopraffazione che subiamo può, in qualche modo, disporci all’azione?” (Idem, pp. 161-64).

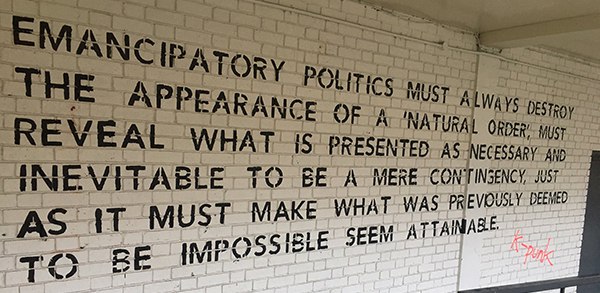

La risposta ultima può essere: si! A patto, però, che si comprenda che “ciò che accade lì accade anche qui”: solo a partire da questo assunto possiamo cogliere “le difficili e mutevoli connessioni globali in modi che ci disvelino l’estasi e il vincolo di ciò che possiamo ancora chiamare etica” (Idem, p. 193). E dunque, anche la risposta alla domanda di Scotini può essere affermativa, ma solo stando alle stesse condizioni. Solo, cioè, se riusciamo a svincolarci dalle prescrizioni incancrenite, ad attraversare le categorie senza impantanarci, ad abitarle temporaneamente senza acquisirne l’abito, a contaminarci della presenza di chi in quel momento le attraversa insieme a noi e contaminare a nostra volta, fintanto che le categorie stesse si trovino violate e private di senso. Non si tratta di disintegrarsi in un nulla totale in cui è impossibile discernere una cosa dall’altra. Nè sto proponendo una via verso il compromesso e la conciliazione a tutti i costi. Partendo da Altaf, anzi, l’incontro che immagino trova nel dialogo uno strumento critico attraverso cui ridiscutere le contraddizioni e le disuguaglianze. Narrazioni catastrofiche a parte, nulla ci impedisce di credere che questo incontro sia ancora possibile. Se l’ipotesi possibilista di sperimentare processi di consapevolezza collettiva, relazioni di cura, politiche situate, sostenibili e continuamente ri-negoziabili ci trovasse dubbiosi o diffidenti, mentre impieghiamo il nostro tempo a capire se siamo ancora o meno in tempo per (re)agire, potremmo sempre supportare quelle pratiche che già esistono, ché non hanno tempo da perdere né paura di fallire: Altaf docet.

In the aftermath of Trump’s victory, with the possible exception of

In the aftermath of Trump’s victory, with the possible exception of

e mid-twentieth century posed the problem of mapping ‘the mathematical properties of the psychological life of populations’ – that is of the psychosocial regulation of social life starting from groups.

e mid-twentieth century posed the problem of mapping ‘the mathematical properties of the psychological life of populations’ – that is of the psychosocial regulation of social life starting from groups.