Author: Tiziana Terranova

Platform Capitalism and the Government of the Social. Facebook’s ‘Global Community’

Some days ago, Facebook’s CEO and founder, Mark Zuckerberg, published on his page a letter where he makes some very interesting statements about the ongoing direction of the platform, its current priorities and the general vision underlyng its strategy of development. The document has been mostly and inevitably read against the larger debate on how the largest of the global social media platforms has changed political communication.

Actually, Zuckerberg does address in the letter two of the most frequent charges which have been moved to the gigantic social networking site by its critics. The first allegation claims that Facebook creates ‘filter bubbles’ and ‘echo chambers’, that is that it exposes its users only to similar opinions (what Zuckerberg names the problem of ‘diversity of viewpoints’, and the ensuing polarization of the political climate). The second accusation concerns the ways in which the medium allegedely does not make a difference between false and true information (as in the virality of ‘fake news’), defined by the American billionaire as the risk of ‘sensationalism’. Defining these issues as basically a question of ‘risks’ and ‘errors’, Facebook promises to invest more into its Artificial Intelligence program, announces great progresses in its capacities to increasingly distinguish ‘true’ and ‘false’ news while also promising to tweak its algorithms to increase the diversity of its users’ feeds – thus addressing the problem of misinformation and political polarization. In addressing these criticisms, what seems to me most significant, however, is the way Facebook seems to admit to be in the unprecedented position to govern the global social life of information, thus becoming the new infrastructure of a transnational, (post)civil society.

It has been quite a change lately from the days when Facebook, following Google in this regard, rejected the idea of being a media company, defining itself first of all as a high tech company. By acknowledging its responsability in creating the social environment or medium where political communication unfolds, Facebook is starting to look more like a medium, hence facing the kind of issues that the news media such as TV or the press have to deal with, such as bias or misinformation. The letter reads as Facebook’s admission that it is willing to take on the political responsability to govern its platform. Technology companies are not new of course to governance – an issue which is keenly felt by businesses operating in the areas of the Internet of Things, Smart City, the Sharing Economy, the Gig economy and so on. Facebook, however, sees itself in the position to regulate what the letter defines as the ‘social fabric’ woven by processes of association and dissociation and the ‘collective values’ that emerge from such processes.

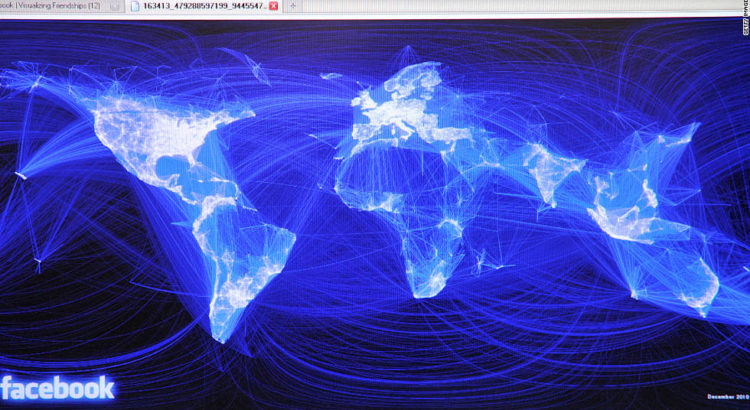

In the aftermath of Trump’s victory, with the possible exception of Uber, mostly Silicon Valley companies have positioned themselves with the opposition, presenting themselves as the stalwart representatives of both American liberal values and globalization (the letter closes with a quote from Abraham Lincoln). If Facebook’s mission is ‘to make the world more open and connected’, then it is a mission which does not agree well with the nationalist closures indicated by events such as Brexit or Trump’s election. The letter presents Facebook as engaged in weaving of a global social fabric which is not homogeneous, but composed of overlapping and yet culturally specific parts. The heterogeneous transnational cultures which make for Facebook’s social fabric produce variable cultural norms, which cannot be determined or governed starting from a single norm. A normative, variable and differentiated curve, such as that described by Foucault in his discussion of mechanisms of security, displaces ‘normality’, while openness and connectedness realize the continuity of economic valorization. (Almost) the whole world, or at least those parts that are ‘open and connected’ is now the ‘inside’ of Facebook – literally lying side by side in its servers.

In the aftermath of Trump’s victory, with the possible exception of Uber, mostly Silicon Valley companies have positioned themselves with the opposition, presenting themselves as the stalwart representatives of both American liberal values and globalization (the letter closes with a quote from Abraham Lincoln). If Facebook’s mission is ‘to make the world more open and connected’, then it is a mission which does not agree well with the nationalist closures indicated by events such as Brexit or Trump’s election. The letter presents Facebook as engaged in weaving of a global social fabric which is not homogeneous, but composed of overlapping and yet culturally specific parts. The heterogeneous transnational cultures which make for Facebook’s social fabric produce variable cultural norms, which cannot be determined or governed starting from a single norm. A normative, variable and differentiated curve, such as that described by Foucault in his discussion of mechanisms of security, displaces ‘normality’, while openness and connectedness realize the continuity of economic valorization. (Almost) the whole world, or at least those parts that are ‘open and connected’ is now the ‘inside’ of Facebook – literally lying side by side in its servers.

A few years ago, authors such as Celia Lury and Maurizio Lazzarato among others, described the change by which post-Fordist businesses do not primarily produce goods, but are engaged in the production of worlds to live in. Here Zuckerberg presents the mission of his company as emtailing a ‘journey’, which involves the creation of a world, obviously open and connected, which realizes the long journey of humanity towards wider and wider forms of social aggregation: from tribes, to cities, to nations, and now, thanks also to Facebook, to a ‘global community’. There is of course more than a a Eurocentric hint of linear progress at work, an arrow of time pointing to the destiny of a global society. Facebook thus presents itself, implicitly like the Silicon Valley as a whole, the historical representative of the forces of globalization which oppose the nationalist closure of Brexit and Trump. Facebook’s mission then becomes implicated in facilitating and expanding globalization as a process which presents ‘challenges’, ‘risks’ and ‘opportunities’ which no single nation or people can take on but that need the mobilization of a ‘global community’.

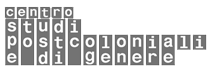

The overall focus of the letter is thus on the challenge of building new ‘social infrastructures’ which enable the global community to get organized and to strengthen the ‘social fabric’ paradoxically compromised by globalization. It’s interesting to notice how this intention to build a global political community is given by data on the growth of ‘groups’ in Facebook. The focus on groups triggers a shift of attention from interpersonal networks (friends and family) and pages (which are the engines of economic valorization with their ‘likes’) towards ‘groups’ as priority for future investment. This shift to groups returns Facebook to questions asked by the inventor of sociometry and of the ‘social graph’, the psychiatrist Jacob Moreno who in th e mid-twentieth century posed the problem of mapping ‘the mathematical properties of the psychological life of populations’ – that is of the psychosocial regulation of social life starting from groups.

e mid-twentieth century posed the problem of mapping ‘the mathematical properties of the psychological life of populations’ – that is of the psychosocial regulation of social life starting from groups.

The question of groups allow for the formulation of the vision and model of society which Facebook proposes as the solution to the global crisis of governance (but significantly not the economic crisis). I am convinced that it is not by chance that the question of the ‘social infrastructure’ has risen around the popularity of groups, and in particular what Zuckerberg defines as ‘very meaningful groups’ which quickly become an essential source of support and identification for those who join them. Unlike interpersonal or egotistic networks (friends, family and acquaintances), groups take us back to the old image of the caring ‘virtual community’ which Howard Rheingold described in the early 1990s. The old virtual community is here integrated into a ‘global social fabric’ which is also an infrastructure which is the platform as a whole. Facebook’s communities or groups are by far the only ways by which communities form on the Internet, but what the company seems to claim is they are in a privileged position to enable such processes within a single, private network with a centralized, cloud computing architecture which hosts a population of a couple of billions of accounts modeled according to the diagrams and methos of graph theory and social network analysis. Such social is not significantly conceived as essentially made of isolated and connected individuals (alone together as Sherry Turkle put it), but as composed of groups and sub-groups. I would argue that in social networks, the individual is always somehow defined by the groups it can be seen to belong too in as much as there is no individual in a social network who exists if not as part of a group – even the smallest group of two. The model of society evoked by Zuckerberg under the name ‘community’ is a set of connected sub-sets, topologically discrete and yet continous which returns the image of an heterogeneous and entangled planet. Implicitly evoking the fist social network analysts, Zuckerberg describes society as a granular fabric of unevenly sized communities, which merge and differentiate, but within a single plateau provided by the platform’s body. One has the impression that it is this specific composition which allows for the social network to become in Zuckerberg’s vision the problem-solving infrastructure of global crises, significantly and mainly identified with terrorism and climate change.

Some years ago, anthropologist and activist Joan Donovan told me how the Occupy movement managed to use and orient politically the logistical capacities of social networks, that is their capacity to change from networks where opinions are shared to networks able to coordinate action at a large scale. When the Sandy hurricane hit New York City, she told me, Occupy managed to collect and distribute resources, thus proving the capacity to produce an autonomous government of emergencies, which national and local government are increasingly inadequate to do because of the budget cuts. In the letter, Zuckerberg keeps quoting examples of such uses of the platform autonomously organized by users, by the intelligence of the general sociality captured by such media. As the number of individuals and groups engaged in thinking and experimenting with p2p and/or -social production grows, Donovan has started to define ‘hypercommon’ the potential of the technosocial to cooperate and govern in ways which differ both from the market and the State’s modalities of government.

Significantly, Zuckerberg does not include in the list of political priorities for the global community the debt crisis, precarity, exploitation or forced migration, but stops at pandemics, terrorism and climate change. The platform thus becomes the was in which an emerging global society defends itself against ‘harms’ and prevents them. If the platform is positioning itself as an alternative to the extreme nationalism of Brexit and Ttump, it does so remaining firmly within the boundaries of what Nick Srnicek has called ‘platform capitalism’ – which will be discussed early in March in an event organized by the free university network of postworkerist inspiration, Euronomade, in Milan’s ‘liberated’ space Macao.

To sum it up, for me this letter makes it even more clear how Silicon Valley is formulating what Foucault would describe as a new ‘political rationality’ which takes on the legacy of liberalism and neoliberalism in identifying as the main problem the government of populations (billions of users), the maximisation of their social, political and cultural life, and the protection from ‘’risks’, ‘harms’ and ‘errors’ inherent in the circulation of information (false news, sensationalism, polarization, divisiveness, terrorism, climate change and pandemics). This is accomplished within a market economy that never questions ownership or accumulation. Together with the smart city movement, platform capitalism intensifies its vocation to become a new form of social government.

I protocolli del potere: Io, Daniel Blake di Ken Loach (2016)

Daniel Blake, il protagonista dell’omonimo film di Ken Loach, è un carpentiere sessantenne, vedovo e senza figli a cui i medici hanno proibito di lavorare a seguito di un serio infarto che l’ha colpito sul lavoro. Per questo si rivolge allo stato sociale per ricevere l’indennità di malattia, un diritto dei lavoratori conquistato, come Loach stesso ha documentato, negli anni seguenti la seconda guerra mondiale sull’onda non solo di un boom economico ma soprattutto della forza e della sicurezza accumulata dalle classi lavoratrici inglesi durante la guerra. Invece di ricevere la sua indennità di malattia che gli avrebbe permesso di recuperare forze e salute, Blake si trova costretto, come molti britannici e non solo, ad attraversare un inferno burocratico dove macchine e umani, computer e ‘professionisti’ si concatenano per impedirgli l’accesso a quello che è un suo diritto.

La prima scena, mentre ancora scorrono i titoli iniziali e non si vedono i volti, ci fa ascoltare un surreale dialogo dove Blake è costretto a rispondere a un barrage di fuoco di domande da parte di una ‘professionista della sanità’ al soldo di una multinazionale americana a cui il governo inglese ha appaltato questo tipo di servizi – domande che nulla hanno a che fare con la sua certificata condizione medica. Il film non ci mostra la figura di questa professionista che nonostante il certificato medico lo dichiara abile al lavoro (che secondo i medici lo ucciderebbe), ma ci fa sentire tutto il peso della violenza dei protocolli che ormai mediano l’esercizio del potere sui corpi della popolazione. I protocolli, infatti, sono sempre più centrali non solo al funzionamento della rete Internet, ma alla trasformazione dei servizi pubblici e dell’assistenza al pubblico secondo i principi del New Public Management. Protocolli e procedure sono delle rigide condificazioni di regole che chi esegue un lavoro di tipo biocognitivo sono sempre più costretti a seguire. Si tratta di un discorso tecnico che può essere formulato da un umano o da una piattaforma informatica ma che comunque si presenta come un monologo con uun feedback o risposta strettamente codificata, dove andare fuori dai binari provoca una punizione o sanzione (per esempio perdere la pensione o sussidio per un mese e quindi la fame). Allo stesso tempo si tratta di un codice soggetto a tutti i bugs o momenti illogici dove i comandi dati sono contraddittori come quando il computer si impalla, ma questa volta quello che si impalla è il sistema burocratico e il costo è la vita o la morte.

Nel film vediamo spesso Blake lottare contemporaneamente contro burocrat*, impiegat* e guardie che continuano a negargli l’accesso all’indennità, costringendolo a fare domanda per il sussidio che a sua volta richiede 35 ore di lavoro settimanale da dimostrare impiegate alla ricerca del lavoro – secondo il regime che ormai si chiama workfare (che costringe a lavorare pur di ricevere un sussidio pur se lavoro non ce n’è, quindi girando a vuoto per esempio). Un abile artigiano che ha usato oltre agli strumenti da carpentiere anche la matita per tutta la sua vita, Blake si trova perso di fronte all’obbligo di usare le interfacce digitali, le piattaforme di stato, per richiedere il suo diritto alla malattia. Il pubblico in sala ride quando lo vede prendere il mouse e metterlo sullo schermo perché non ha mai usato un computer e freme empaticamente di frustrazione quando lo vede aspettare per ore che qualcuno risponda a un call centre a pagamento che gestisce i ricorsi o quando lo vede affannarsi per ore al computer solo per sentirsi dire che la sua sessione è scaduta per mancanza di tempo o che c’è un’errore nel suo modulo o che il computer si è impallato. Protocolli, piattaforme, regole e impiegati ridotti ad automi si compongono in una macchina crudele, sadica che, come rileva il ragazzo nero vicino di casa di Blake, serve solo ad umiliare ed ‘eliminare’ quanti più possibili ‘numeri’ (statistiche) dal sistema. E’ contro questa macchina infernale che si presenta come ‘morale’ che Blake compie la sua trasgressione più grande: scrivere con una bomboletta spray a grandi lettere calligrafiche la sua richiesta di indennità di malattia sul muro dell’ufficio tra le acclamazioni e i cori anti-polizia della folla del centro della città.

D’altro canto però Loach, nella tradizione dei grandi storici inglesi della classe operaia come Richard Hoggarth e E.P. Thompson, non lascia solo il suo Blake davanti alla macchina sadica del workfare. Mentre ci mostra l’incubo di una rete asservita al potere, ci mostra anche tutta l’importanza e la vitalità delle comunità operaie del nord dell’Inghilterra, delle reti sociali di assistenza e aiuto reciproco, degli atti di quotidiana gentilezza e di sostegno che si esprimono anche come ribellione – come quando Blake si alza nell’ufficio comunale per chiedere che la ragazza madre di due figli che è arrivata tardi perchè trasferitasi da poco da Londra e poco avezza ai mezzi, possa avere il suo appuntamento, chiedendo agli astanti di lasciarla passare e quindi ricevere il sussidio di cui ha bisogno per sfamare sé stessa e i figli. Non ci sono deroghe alle regole però, e tutt’e due vengono buttati fuori dalle guardie giurate, diventando però amici con Blake che darà sostegno pratico e affettivo alla giovane famiglia. La ragazza infatti è stata sfrattata da Londra insieme ai due figli, costretta a trasferirsi per uscire dall’ostello e avere una casa per sé e i suoi figli. Come le nostre insegnanti, lei perde la sua rete familiare e di sostegno, cacciata dagli affitti alti, dalla mancanza di edilizia popolare e dalla tassa imposta dai conservatori sulle cosiddette ‘stanze sfitte’. La rete sociale della solidarietà operaia e dell’aiuto reciproco contro la rigidità delle regole e delle piattaforme di stato è basata in rapporti di vicinato, in gentilezze quotidiane, ma non è di per sé a-conflittuale o tecnofoba. Dopo lo scontro con il modulo online per fare domanda di disoccupazione, Blake si ritrova a passare una serata gioiosa con i suoi due vicini di casa, due ragazzi magazzinieri , in collegamento diretto su skype con un operaio cinese fan di calcio, che gli manda di nascosto le costosissime trainers che loro rivendono a metà del prezzo del negozio. Alle regole rigide del potere, ai suoi protocolli e al suo sadismo, Loach oppone dunque una rete fatta di solidarietà e aiuto reciproco e una tecnocultura artigianale che plasma il legno e cura le relazioni ma che usa anche la logistica della rete per creare nuovi legami transnazionali di un commercio solidale e anti-legalitario.

Blogging…

It’s the afternoon of a warm October day, teaching term has just started and we are sitting in my living room, Stamatia Portanova, Roberto Terracciano, and myself. The three of us are about to launch the official blog of the Technoculture Research Unit – a group born within the Centre for Postcolonial and Gender Studies directed by Iain Chambers, at L’Orientale University in Naples. Many of the members of the group have been PhD students in the programme in Cultural and Postcolonial Studies of the Anglophone world at L’Orientale over the past ten years and now are living a more or less precarious scattered existence in schools, universities, research centres all over Europe, striving to do research amidst the necessity to make a living somehow. We came together as a group of researchers working at the intersection of cultural/postcolonial studies, feminism and new media studies. As the PhD programme succumbed to cuts and the Gelmini law, there is a ‘we’ out there that refuses to dissolve, which cannot be satisfied living as a series of scattered ‘I’s – at least in relation to the field of studies we all love. The blog is a way to exit both the narrow possibilities for expression afforded by a platform such as Facebook, but also to find each other again, to find some kind of resonance in our different voices. ‘How to Make a We in a (Social) Network Culture’, for example, could be the title of an article I am planning to write with a member of TRU, Antonia Anna (Nina) Ferrante, about the Netflix hit Sense8. The relation between singularity and universality, the individual and the group in these new technocultural conditions seems to me an absolutely central question and one I would like to develop further in these short blog entries for the TRU blog.